Demanding nothing in return for his kindness, the sage eventually obtains everything;

The sage does not accumulate things,

Yet the more he gives to others, the more he has himself.Having given to others, he is richer still.

Laozi from Dao De Jing

Why haven’t I read this sooner.

The quote above is from the University of British Columbia (UBC) Professor Edward Slingerland’s Trying Not to Try: The Art and Science of Spontaneity. As the title of this post suggests, it is one of the best books about the psychology of the mind I have read. Slingerland is also Professor of Asian Studies and Canada Research Chair in Chinese Thought and Embodied Cognition at UBC. As his academic title suggests, he is a world renowned expert on the relations between ancient Eastern thoughts and modern cognitive science. The quote above is from Laozi (or Lao-tzu, who lived approx. 6th century B.C.E.). He’s the master of Daoism who, as the legend goes, left us with just one Chinese text where the quote above appeared, better known in the West as the Dao De Jing (some translated as “the way of life”).

In fact, I came across his online course Chinese Thought: Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Science before on the EdX platform when I was teaching an introductory course in philosophy a few years back, but I didn’t seriously follow up on it (the course, by the way, is still free, and is great, so I highly recommend to everyone). Why is Trying Not to Try and his work so great? Because it tells us not only why the ancient wisdom of “trying not to try” is right and that the modern idea of “trying your best” is wrong, and how me might make use of the ancient wisdom to make our life today more fulfilling — but through the lenses of modern science. So, even those who may not have the stomach to swallow “ancient Chinese thoughts,” this book can show you through modern scientific ideas how we can practically improve our well-being.

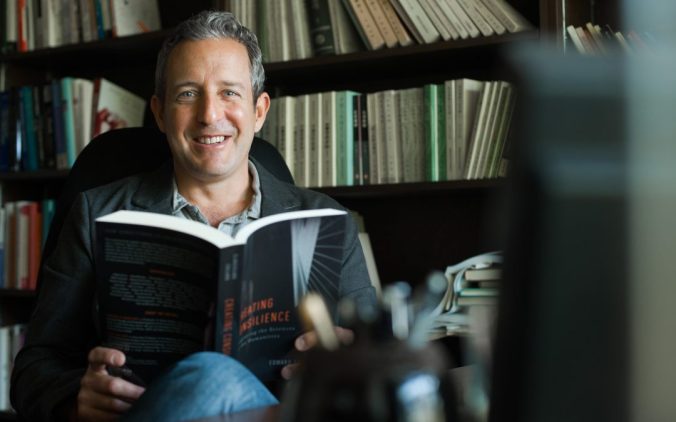

Professor Edward Slingerland before giving his lecture “Trying Not to Try: Early China, Modern Science.” Photo Courtesy of TEDx Maastricht. I highly recommend his EdX course. Apart from his great knowledge, he also has a great voice and is extremely witty in his teaching of such a difficult and complicated subject.

Actually, I wasn’t planning on reading this book at all. I stumbled upon Trying Not to Try while searching for books to read as I was preparing to get on a 14-hour-long cross-country train to travel to work. I didn’t realize that this book had been in my wish list for years, until an automatic message from Amazon.com app reminded me that this book was on sale. I “didn’t try hard” to find a book to read, so I came across this book. Had I “tried harder,” I would have read multiple reviews of multiple books, by multiple authors, and then evaluated which book to buy based on those reviews once they’re mentally tabulated in my mind for a proper cost-benefit analysis. I probably ended up with a different book if I “had tried to hard.” So, because I didn’t try to hard, I thought I could “give Trying Not to Try a try.”

Trying Not to Try has confirmed a lot of things I have always firmly believed about how a life should be lived. And yes, I am aware of the so-called “confirmation bias.” Just because a book confirms my preconception about something doesn’t (and definitely shouldn’t) automatically render it right, right away. I read Trying Not to Try twice during my 14-hour-long journey (yep, it’s a really long train ride) to make sure that what I agreed with about the idea of “trying not to try” is the best way of achieving just about anything is not just a confirmation bias. For instance, the idea that the best action is, surprising to many, a “non-action.” The more we try to do things, the more we usually end up leave things undone. We are living in the world in which most of us are encouraged to “be better than others,” “do more than others,” “get ahead of others.”

The logic behind this? Simple. The idea of “better” is relative, the underlying reason for all of these is to be “better,” which, in essence, is all about comparing yourself to others by ways of the result. When we want to be better, we automatically (and unconsciously) shift our focus from the task at hand to our expectation.

And as modern psychology (as well as behavioral economics) shows, when the task at hand is not received enough attention from us, it often results, ultimately, in failure – sometimes not only that task at hand, but also other related tasks as well. Professor Slingerland uses many examples such as basketball players and golfers who were “in the zone” – playing their best games naturally – only until someone reminded that them that they should “try to keep up with their game.” That’s when the “hot hand” was forced to make error. These players started to make mistakes, mostly unforced (known as “choking”) leading not only to the bad result but also the end of the focus on the task. So, why is “trying” so harmful to what we want to do? Why shouldn’t we be trying? And, ultimately, what exactly is to “try not to try?”

The writing is on the tombstone “Don’t Try.” Photo courtesy of Charles Bukowski Appreciation Thread.

I have been thinking about the question ever since I learned from the author (and a modern Daoist philosopher) Mark Manson’s best-selling The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck that on the tombstone of the legendary writer and poet Charles Bukowski writes “Don’t Try.” I wrote about this in my earlier blog post but I did not further explore what it actually means, perhaps because I did not know what it really meant. Manson, using this same example, of the tombstone writes what he understands:

Bukowski’s life embodies [what seemingly sounds like] the American Dream: a man fights for what he wants, never gives up, and eventually achieves his wildest dreams. It’s practically a movie waiting to happen. We all look at stories like Bukowski’s and say, “See? He never gave up. He never stopped trying. He always believed in himself. He persisted against all the odds and made something of himself!”

It is then strange that on Bukowski’s tombstone, the epitaph reads: “Don’t try.”

See, despite the book sales and the fame, Bukowski was a loser. He knew it. And his success stemmed not from some determination to be a winner, but from the fact that he knew he was a loser, accepted it, and then wrote honestly about it. He never tried to be anything other than what he was. The genius in Bukowski’s work was not in overcoming unbelievable odds or developing himself into a shining literary light. It was the opposite. It was his simple ability to be completely, unflinchingly honest with himself—especially the worst parts of himself—and to share his failings without hesitation or doubt.

This is the real story of Bukowski’s success: his comfort with himself as a failure. Bukowski didn’t give a fuck about success. Even after his fame, he still showed up to poetry readings hammered and verbally abused people in his audience. He still exposed himself in public and tried to sleep with every woman he could find. Fame and success didn’t make him a better person. Nor was it by becoming a better person that he became famous and successful. Self-improvement and success often occur together. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re the same thing.

The story of Charles Bukowski is deeply interesting because it creates, almost instantly, the sense of “cognitive dissonance,” or the state of having inconsistent thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes, especially as relating to behavioral decisions, in our mind. How can someone who simply did what he liked, and never tried harder, became more and more successful as he life progressed? Shouldn’t it be the other way around, as in, we must strive harder and harder and perhaps never stop? What’s the deal with his success?

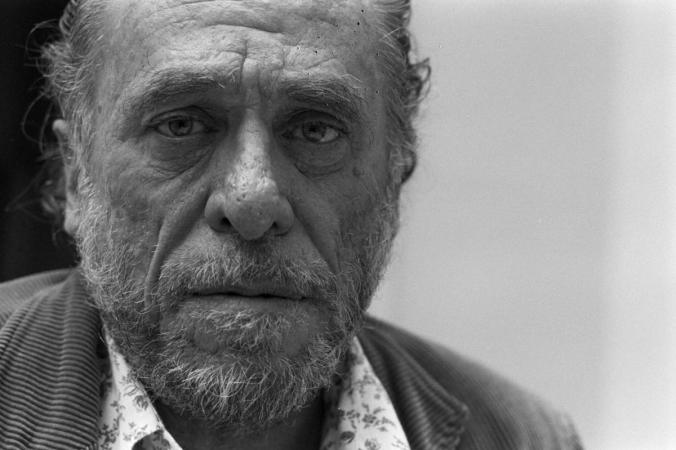

Charles Bukowski. Photo courtesy of the Poetry Foundation.

Bukowski didn’t give a fuck about success? Interesting. We might be able to understand why he became successful without even trying. In fact, if we look at modern research from a psychological perspective, backed by scientific research, we humans are:

-

At best at what we do when we are in the “flow” (some use the idiom “in the zone” which have a similar meaning; a psychological concept of deep engagement coined by):

-

At best at what we do when we are not doing it for external rewards or results, but for our own need to fulfill our internal desire; in other words, we are at best at what we do when we, simply, enjoy doing it;

-

At best at what we do when we do it with a clear, not clouded, mind. Our mind can be clouded by all kinds of thoughts including getting a reward; and,

-

At best at what we do when we do it for a purpose larger than ourselves.

There’re a long list of scientific researches from various fields that support these following findings (with which I can provide you; just write me directly to save space). I remember a countless time seeing someone’s doing something so brilliantly, but only until they’re being “applauded” for the work that they do that their brilliance begins to fall apart. Needless to say, it also happens to me a countless time, which may have been the reason for why I have been taking the “non-consequentialist” approach to doing things.

A consequentialist believes that the worthiness of an action is to be judged solely by its consequences.

I, too, used to be a consequentialist.

I used to do things because I wanted a good result, praise, and rewards. And as you may guess, I never got anywhere with my life. I tried to recall when I became an anti-consequentialist, but still couldn’t recall when exactly that I changed. A guess is that it could have been that moment about a decade back when I heard about the reason why the acclaimed director, writer, actor, etc., Woody Allen has never accepted any awards — including 4 Academy Awards (yes, the Oscars), 10 BAFTA awards, and 2 Golden Globe Awards. Why? He remarkable said toABC News in 1974:

The whole concept of awards is silly. I cannot abide by the judgment of other people, because if you accept it when they say you deserve an award, then you have to accept it when they say you don’t.

So, Woody Allen (by the way, my favorite movie of his is not Annie Hall, but Whatever Works) never shows up to receive any awards for which he has been nominated. In fact, many critics have already given up on convincing him to “just take the Oscar already” (The magazine Atlantic Monthly, in fact, cries out loud: “Stop Giving Woody Allen Awards, He Won’t Show Up Anyway”). In the sense, Woody is right to have his own standard by which he aspires his work to live. But more to that is the fact that he doesn’t work for any recognition except his own — and he’s remarkably successful. He even implies that indulgences in awards can make you less efficient. Is that true, through?

The genius who disdains the idea of getting an award — from anyone.

Why exactly do rewards make us less efficient?

From an economic perspective, it should be the opposite, isn’t it? Economists believe that humans are driven by incentives. Give them the right incentives and they’ll collaborate, manufacture, and come up with great ideas. But historically, though, I have to say that’s not how great ideas and performances come about. The best-selling author and entrepreneur Rolf Dobelli has for us a succinct answer. He writes in The Art of Thinking Clearly:

Science has a name for this phenomenon: motivation crowding. When people do something for well-meaning, non-monetary reasons —out of the goodness of their hearts, so to speak— payments throw a wrench into the works. Financial reward erodes any other motivations.

So who is safe from motivation crowding? This tip should help: Do you know any private bankers, insurance agents, or financial auditors who do their jobs out of passion or who believe in a higher mission? I don’t. Financial incentives and performance bonuses work well in industries with generally uninspiring jobs—industries where employees aren’t proud of the products or the companies and do the work simply because they get a paycheck. On the other hand, if you create a start-up, you would be wise to enlist employee enthusiasm to promote the company’s endeavor rather than try to entice employees with juicy bonuses, which you couldn’t pay anyway.

That is to say, rewards, financial incentives, and material results are not the reason that motivate people to do great thing, or the cause of how great ideas come about. They are the reason that makes the focus of the doers shift from that of the “unconscious passion” to that of the “conscious consequentialist.” As science shows, we automatically let go of the mental capacity to perform once that happens. The legendary swimmer Michael Phelps, too, always remind us of how he never aims at getting a medal when he swims: “I enjoy swimming and it’s just a routine.” Just a routine? — He’s the most decorated Olympian of all time, with a total of 28 Olympics medals! Great minds, pioneers, athletes are those who do what they do because they, “simply” enjoy doing it, and because of that some of them are even excellent in what they do and therefore contribute hugely to the community and society in which they live.

Let me return, on more time, to the ancient Chinese philosopher Laozi’s view on why “conscious effort” (the trying to hard) and especially those who “strive are responsible for the world’s ills” are actually not as useful as they think. Slingerland translates the following:

The highest Virtue [de] does not try to be virtuous, and so really possesses Virtue.

The worst kind of Virtue never stops striving for Virtue, and so never achieves Virtue.

The person of highest Virtue does not act [wu-wei] and does not reflect upon what he is doing.

The person of highest benevolence acts, but does not reflect;

The person of highest righteousness acts, and is full of self-consciousness.

Starting from today, I am going to try not to try.